- Home

- Hollis Gillespie

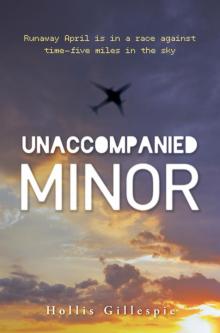

Unaccompanied Minor

Unaccompanied Minor Read online

UNACCOMPANIED MINOR

HOLLIS GILLESPIE

F+W Media, Inc.

Contents

Title Page

Part I: The Incident Reports

Part II: The Accident Report

Part III: The Guardian Ad Litem

Part IV: The Statement

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Part V: The Kidnapping

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part VI: The Bomb Threats

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Part VII: The Bomb

Chapter 11

Part VIII: The Guns

Chapter 12

Part IX: How to Throw a Dead Body Off an Aircraft

Part X: The Cockpit Breach

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Part XI: The Landing

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Part XII: The Term Paper

Copyright

PART I

THE INCIDENT REPORTS

WorldAir Accident and Incident Report

Flight 1021, ATL–LAX, April 1, 2013, 11:15 A.M.

FTA Telex number 880002215

Level 3 Threat

Flight attendant found note placed on seat 42A:

“There is a bomb on board this plane! Not kidding!”

* * *

Unknown Male

Tuscaloosa Homicide Incident Report

April 1, 2013, 11:54 A.M.

Incident # 880002145

Type of incident: Homicide.

Type of call: Disturbance—described as “debris” falling from the air. Upon arrival at the scene, “debris” was discovered to be a deceased male. The body landed on a blue Toyota Prius from what must have been an enormous height. The Prius is now demolished.

Address of incident: Whole Foods parking lot, 1099 Roosevelt Ave., Tuscaloosa, AL.

Subject class: Victim, unknown male, Caucasian, approx. 5'10", 180 lbs.

Identifying marks: Three black crows tattooed on neck. Writing on back of shirt in red marker: “WorldAir flight 1021. We are being hijacked. Please don’t shoot us down! Call 404-828-8805.”

* * *

WorldAir Accident and Incident Report

Flight 1021, ATL–LAX, April 1, 2013, 12:01 P.M.

FTA Telex number 880002216

Level 4 Threat

Flight Deck has been breached.

Tower lost cockpit communication with WorldAir L-1011 flight 1021 at 11:50 A.M. Homeland Security notified 11:52 A.M. Countermeasures deployed 11:59 A.M.

* * *

FBI Telephone Conversation Transcript

404-828-8805

04/01/2013, 12:20 P.M.

[phone ringing]

Unknown female:

Hello?

Agent Anthony Kowalski:

Who the hell is this, and why is this number written on the chest of a dead FBI informant?

Unknown female:

He was an FBI informant?

Kowalski:

I’ll ask the questions, kiddo! Who the hell are you?

Unknown female:

My name is April Manning. I’m on WorldAir flight 1021. You lost all cockpit communication with us about twenty minutes ago.

Kowalski:

How the hell do you know that?

April Manning:

Because I’m the one who destroyed the airplane’s radio signal.

PART II

THE ACCIDENT REPORT

Preliminary Accident Report

WorldAir flight 1021, April 1, 2013

Present at transcript:

April May Manning, unaccompanied minor

Detective Jolette Henry, Albuquerque Police Department

Investigator Peter DeAngelo, NTSB

My name is April Mae Manning—M-a-e, not “May” as in the month. The investigators had it wrong, incorrect, on the police report, and the distinction is probably important. I pointed it out to them because I just wanted to make sure they knew I was cooperating here, okay? And, by the way, I stated from the start that I know bombs are a bad idea. A very, very bad idea.

Investigator DeAngelo:

Okay, let’s try to focus on the events as they transpired, shall we?

April Manning:

Bomb threats, though, have their uses—they really do—and I could probably expound on that later. First, I want to point out that if everything had gone according to the WorldAir flight attendant manual, we would not have been looking at such a disaster here. And I say “disaster” only to quote the president of the airline, because I overheard him outside the interview chamber just now shouting about what a “disaster” all of this is. Why don’t they just call this an “interrogation” chamber? That’s what it is, isn’t it? I seriously hate euphemisms.

DeAngelo:

The question was, how did you break into the cockpit?

April Manning:

Let me explain from the beginning. So, here’s the deal. We see things differently, the WorldAir president and I, about this so-called disaster. It could have been much worse, if you ask me, and that is really what you should be asking me, as opposed to interrogating me. By the way, right now I’m practicing the recommended co-parenting method of disagreement. That’s to say, “We see things differently,” as opposed to screaming and engaging in acts of petty-to-midlevel violence, like the time my mother drove Ash’s new Jeep through the sunroom, or when Ash backed a dump truck over my mom’s freshly planted azalea bushes to fill her swimming pool with pea gravel. I don’t think the instructions of the co-parenting counselor stuck very well with either of them, but I personally like this particular piece of advice, to say, “We see things differently.” I use it all the time, because for one it really does dissipate arguments, and for another, the mere utterance of the phrase infuriates each of my parents.

“Your future stepmother is getting promoted to partner in her law firm,” Ash would e-mail me. “She says it’s important for you to be at the banquet.”

“We see things differently,” I’d respond, prompting a barrage of vitriolic e-mails in return.

Just to be clear, I’d been told by the family court-appointed specialist that the hateful thoughts I have for Ash and his girlfriend are normal, which was a relief, because I’d spent way too much time on them. Especially after I read the guardian ad litem’s report that was submitted to the judge. A guardian ad litem, or GAL, is someone appointed by the judge during a divorce case to write a report recommending who gets custody of the kids, and it’s all based on what is supposed to be in the best interests of the child. In my case, the GAL said she had interviewed me, which was funny because I never met her, ever, and I’m not exactly a forgetful type of person. To say the least.

For example, I still remember my real father, and I was barely five when he died. He was a WorldAir flight attendant as well, and I remember the morning he left to work a flight to Orlando. I know it was Orlando because we’d just gotten back from Disney World and I begged to go back with him so badly that I almost got my way. He had already caved and was at his computer to check the counts on the flight to see if Mom and I had a chance of getting on.

But the flight was oversold. “Dang. There’s two high-school groups and a giant mess of cruise passengers. Maybe next time, Beanie Baby,” he said to me. He had a lot of nicknames for me. I remember them all: Beanie Baby, Bean, Taz (short for Tasmanian Devil), Dimples (I have some), and so on. (I was five, okay?) The morning he left h

e kissed me on each of my eyelids and told me to take care of my mother. I promised I would. That was ten years ago. And I kept the promise, too, believe me. I’m still trying to keep it, because it’s a big responsibility that comes with being the last of a pedigreed airline lineage.

That morning, my father also gave me a foreign coin that was silver but for a small gold circle at the center. He said it reminded him of his two girls, Silvy and Goldie. Goldie is another nickname for me because of the color of my hair, and he called my mom Silvy sometimes on account of the color of hers, and you have to admit it is kind of unusual for the two of us to be silver- and gold-headed. My mother used to have hair my color until she had me, then it started growing out all shiny and silver. Not gray, but silver. Platinum. Looking like it was dyed that way. She wanted to dye it back to blonde but my father begged her not to, and I don’t blame him; it was the prettiest color hair I’d ever seen. People constantly complimented her on it, and when she put on her uniform she always wore her hair in a thick French twist fastened in the back with a small chopstick. I guess when your hair is really thick you don’t need much to keep it nice and knotted. Me, I wouldn’t know. Mine’s like corn silk, a bunch of hair but thin. She had a lot of pretty hair sticks. Dad picked them up for her whenever he worked a flight to Japan.

And another thing: my mother did not use the regular-size chopstick, but the kind made for little Asian children’s hands. The other kind were too big; they stuck out too far. I’m not getting off-track here. All this is pertinent information. It’s “germane” to the topic. I had to look up the word “germane” when I read the guardian ad litem’s recommendation. It stuck in my head.

When she married Ash, he pressured her to dye her hair.

That’s why it matches mine again. That’s why I can use her badge.

DeAngelo:

April, the cockpit? How did you get in?

April Manning:

I can’t take all the credit. I had help from my friend Malcolm Colgate. It’s ironic, because Malcolm always used to tease me for being super-hyper safety conscious. For example, I hate it when passengers grumble about having to put their seats and tray tables upright during takeoff and landing. The extra three inches of velocity of a reclined seat during an impact could mean the difference between snapped and unsnapped neck vertebrae. And that lowered tray table? It could cause a spontaneous appendectomy. I don’t want to be slipping and sliding all over the paralyzed and bisected body parts of these idiots while I’m trying to outrun the ball of fire coming through the fuselage.

“I can’t believe you’re afraid to fly,” Malcolm liked to tease me. “Oooh, what’s that? I think I smell smoke!”

“I’m not afraid to fly!” I’d protest. It’s true. I’m not. It’s just that you can’t come from a long pedigreed airline lineage without hearing all the stories. Like how that big crash in New Orleans in the late seventies could have been avoided if only the ground crew had put the correct fuel in the tanks. Or how that giant crash in Mexico City happened because the idiot air traffic controller directed the pilot to land on a runway that was under construction. Like I said, I have a hard time trusting people, and almost all airplane crashes are due to stupid things people do. Just thinking about it would make me ask Malcolm if I could hold Captain Beefheart, the emotional support dog he always got to bring onboard with him. Lately Malcolm has gotten into the habit of just handing Beefheart over to me as soon as we got situated in our seats. I am grateful for that. That dog is oddly calm. And I think he purrs. Can dogs purr?

Inspector DeAngelo:

I don’t think so.

April Manning:

I swear this one does. Anyway, Malcolm and I like to compete with each other on our knowledge of airplane wrecks. I consider it extreme flirting. Maybe I should let him win once in a while, because he seriously couldn’t hold a match to me.

“Dallas, flight 191,” he challenged a few months ago as I took my assigned seat next to him.

“What is this, amateur hour?” I smiled. “Wind shear. Lockheed-1011 TriStar. The second biggest death toll involving an L-1011 in history.” The legacy from that crash has probably saved thousands of lives since then.

Inspector DeAngelo:

What’s the legacy?

April Manning:

The legacy is that now all aircraft are equipped with Doppler radar that can detect changes in wind patterns as well as weather patterns.

“Right?” I asked Malcolm.

“Correct,” he applauded me.

Malcolm and I had started including the legacies of plane wrecks after a deadheading pilot once joined our conversation and informed us that, on certain DC-9s, you could still find raised Braille-like symbols on the strips right below the overhead bins that were meant to allow passengers to feel their way out of a smoke-filled cabin, should the need arise. Well, naturally the day came when a DC-9 crashed and the need arose. Then the National Transportation and Safety Bureau (NTSB) discovered that, because smoke rises, the last thing they wanted was passengers standing up filling their lungs with it as they groped for tangible indicators to guide them to safety. After that the indicators were put along the floor, such as the “white lights that lead to red lights indicating the exits” strips you hear about in the safety demonstrations of some older-model jets.

But then of course an air crash came that tested the newer method, and it was discovered that, while smoke rises, noxious fumes sink. So the least desirable place now for passengers in a crash situation was for them to be groveling with their noses to the ground, inhaling the poisonous fumes billowing down from the melting synthetic polymers airlines use to manufacture their seat covers. So today the standard is for planes to have indicators that light up at “armrest level,” because that air—between the rising smoke and the sinking fumes—that air is the safest. Or at least it is until we learn differently.

So it was the “legacy” of each plane wreck that allowed for that much safer air travel afterward, and so on and so on, because in the end air travel is really just a giant ongoing human experiment. I suspect Malcolm finds it fascinating because he is a boy and that’s how his mind works. I am fascinated by aviation disaster legacies, of course, because my real father died in a plane crash.

Or I should be specific and say he died “due to” a plane crash, because, of course, he survived the impact; almost everybody on board did. But instead of jumping down the inflatable slide to the safety of the tarmac below, my father went to assist some passengers in the back of the plane whose evacuation was being obstructed somehow—and that was it. The fuel in the wings ignited and the plane was engulfed before the firemen could unroll their hoses. Anyone who hadn’t made it out by then didn’t make it at all.

And the obstruction that impeded the evacuation? A few passengers were clamoring to get their bags from the overhead bins. I guess some people have no “situational awareness,” as the flight attendant handbook instructs us about. They think they have time. They don’t understand the obvious dangers. My father understood the dangers, though, and still he went back to urge them forward. One wrong step is all it took. In instead of out. Forward instead of back.

Today, when flight attendants attend their mandatory annual training to update their skills, among the set of crash commands they are instructed to shout during impact—commands such as “Heads down!” and “Get up! Get out!”—there is a new command, and that command is “Leave everything!”

In the number of airline accidents since, it comforts me to think my father contributed to the revised safety measures that may have saved some people. This is another reason I am so obsessed with safety. My father literally died for this, so every time I badger a fellow passenger to put up their tray table or secure their carry-on or whatever, I am honoring my dad’s legacy.

I was glad to see Malcolm on my flight, because I could never be sure he’d be booked. Unlike the gate agents, I can’t pull up the passenger names. I can only pull up the crew manifests t

o see who is working the flight, which is why I can almost always book myself on a flight that Flo is working. But in Malcolm’s case, I know how to decipher patterns, and Malcolm’s parents have a pattern of putting him on late-afternoon flights on large-body aircraft. I suspect it’s because they are using their frequent-flyer miles, and the bigger the airplane the bigger the likelihood for frequent-flyer seats.

Unaccompanied minors are usually seated together or with an employee flying nonrevenue if possible, so Malcolm and I are often assigned seats next to each other. Along with plane-wreck trivia, we like to compare divorce notes. For example, during his supposed interview with his court-appointed guardian ad litem, she gave him some Sharpie markers and said, “I hear you like to draw,” and that was it, the whole interview. Then his dad’s private investigator produced pictures of the GAL engaged in acrobatic sex with Malcolm’s mother’s attorney in the front seat of his Lexus. The judge of course threw out the report and his dad got shared custody. It’s why Malcolm is always on the plane like I am. Our parents live across the country from each other. It’s why we’re always flying back and forth. It’s also why we both go to the same school, an online academy that is part of the Atlanta public school system. It’s the only way we can stay current in our studies while bouncing from coast to coast.

The difference between Malcolm and me, of course, and I’m sure you knew this, is that Malcolm flies full fare, while I fly nonrevenue. Still, though, he is the only friend I have who relates to my parenting situation.

PART III

THE GUARDIAN AD LITEM

FBI File Documents

1. Personal letter and court document, augmented

Received by Fulton County Judge Jonathan Cheevers via UPS, postmarked 12/13/2012

Custody recommendation of Catherine Galleon, guardian ad litem re Manning vs. Manning Fulton County Family Court Case # 708621

Red-marker margin notations inserted post submission by April Mae Manning

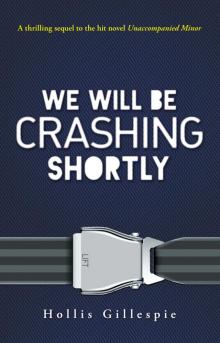

We Will Be Crashing Shortly

We Will Be Crashing Shortly Confessions of a Recovering Slut

Confessions of a Recovering Slut Unaccompanied Minor

Unaccompanied Minor Bleachy-Haired Honky Bitch

Bleachy-Haired Honky Bitch